Stripped down ‘3.0’ tour at the Auditorium shows a Sting in top condition ...

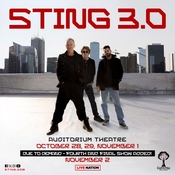

If you’re looking for a musical example of the practical and creative benefits of maintaining a healthy lifestyle, Sting provided it Tuesday night at a packed Auditorium Theatre. Appearing at the historic venue on the second of a four-night run on his “Sting 3.0” tour, the 73-year-old icon played with a rousing blend of energy, finesse and muscularity that mirrored his athletic physique.

Whether owing to his fit-and-trim condition, his stellar band or a relatively recent decision to return to his roots by stripping down his songs and group to core essentials, Sting made a primarily nostalgic set feel vibrant, punchy and direct. Accompanied by drummer Chris Maas and longtime guitarist/collaborator Dominic Miller, the singer-bassist disposed of the gussied-up arrangements, big ensembles and oft-ponderous techniques that marked past tours.

What remained were his famously elevated standards. While that meant assuredness trumped risk-taking, Sting’s ongoing quest for perfection came through in the brilliantly rendered shape, balance and color of nearly every note the trio played. Plus, the clarity, crispness and separation of the mix — combined with terrific room acoustics — ensured that even fans seated toward the back heard the unusually broad scope of dynamics on offer.

Those extended to Sting’s strong, well-preserved vocals. Easy as it would have been to do, the British native resisted any temptation to operate on autopilot. Save for marginally deepening and no longer reaching the highest peaks on classics such as “Tea in the Sahara,” climbs he abandoned years ago, the majority of his mid and lower range sounds nearly indistinguishable from the era in which he sported shoulder-length hair. Specifically, the late ‘80s, the only other time he performed at the Auditorium as a special guest of headliner Frank Zappa.

Unlike the late, outspoken Zappa, Sting refrained from discussing politics and excused himself from weighing in on the election due to his English citizenship. Nonetheless, he enriched the two-hour concert with concise, between-song banter that addressed lyrical origins, his background and recollections. Predictably calm and serious, Sting managed to display genuine gratitude and shared a few witty remarks that indirectly referenced his own fortune.

At this juncture of his career, Sting has nothing left to prove. Think of a major prize and he’s probably won it. In addition to nominations for Academy and Tony Awards, he’s earned 17 Grammy Awards, three Brit Awards, the Polar Music Prize, an Emmy Award, a Golden Globe Award, an American Screenwriters Award, Billboard Music Century Award … you get the picture.

The singer-songwriter born Gordon Sumner stands as one of the most decorated artists of any generation. Add in his CBE and Kennedy Center honor and it’s understandable that some detractors dismiss him as intolerably arrogant.

There also remains the matter of The Police. In the eyes of many fans, he endures as a Yoko Ono-esque figure responsible for causing the band to break up at its zenith. Then again, what internationally renowned musician doesn’t possess a sizable ego? It comes with the territory and, fairly or not, gets celebrated as an advantage in other genres.

To Sting’s credit, he’s been unafraid to attempt an array of other pursuits, whether in the guise of a Broadway musical (“The Last Ship”), exploratory if tedious albums (“Songs from the Labyrinth,” “If on a Winter’s Night…”) or unexpected collaborations (the “44/786” LP with Shaggy). Further evidence Sting might not entirely deserve his stuffy reputation: His self-aware role in 2021 in the first season of “Only Murders in the Building.”

On Tuesday, those excursions seemed a world away, perhaps deemed unsuitable for the bare-bones trio configuration and its focus on recognizable rock-based fare. With the exception of the insistent “Never Coming Home” and a convincing rendition of the 2024 single “I Wrote Your Name (Upon My Heart),” every tune the band chose dated from the prior century. The oldest work, “I Burn for You,” doubled as the deepest cut, initially recorded in the early ‘80s by The Police for a film soundtrack (“Brimstone & Treacle”) and later released as a B-side.

Refreshingly, the group approached the music (largely split between solo favorites and Police standards) with a steady purpose and an open-minded attitude that the songs still may have something new to reveal. That premonition paid dividends.

In parallel with their locked-down interplay, the band illuminated the superb craftsmanship — the infectious melodies, the momentum-building bridges, the staggered rhythms, the intentional spaces, the slippery grooves, the seamless fusion of jazz, pop, rock and reggae — at the center of the familiar songs. Despite sounding like their architecture owed to an elemental simplicity, deceivingly complex material such as the gorgeously understated “Fields of Gold,” solemn “Why Should I Cry for You?” and temperamental “King of Pain” demanded flexibility, accuracy, contrast, sophistication and a knack for managing quiet tension. Sting and company delivered.

Casually dressed in a T-shirt and jeans, the sinewy singer used a microphone headset that allowed him to roam freely on the no-frills stage. Unless holding his instrument at a 45-degree angle counts, Sting never called attention to his fluid, thumb-driven bass playing. Akin to a magnet, it pushed and pulled songs in intriguing directions. Its nimble, jazz-bent phrasing governed tempos and echoed during elegant ballads (“Shape of My Heart”), urgent anthems (“So Lonely”) and declarative odes that invited mass sing-a-longs (“Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic”).

Miller, a tested veteran of Sting-fronted bands, served as a tonal wizard whose guitar stood in for keyboard, horn, piano and string parts. Practicing an efficient economy of scale that witnessed him refrain from adding superfluous fills or extraneous chords, Miller epitomized the art of graceful minimalism. He supplied atmospheric rivers of textures, harmonics and effects, and stepped out for a couple of sizzling solos, accomplishing everything with foot pedals and one Stratocaster.

A drummer to watch in the future, Maas handled countless time-signature changes with equally modest prowess. He also brought satisfying measures of force and pressure to the songs. Maas’ sharp percussive strikes registered with noticeable weight, and the seven-cymbal array on his kit allowed him to signal transitions with splashy accents, powder-coat choruses with a metallic-flaked shimmer and complete finales with crashing punctuation.

A knotty, progressive-minded “Seven Days” executed in 5/4 time and extended, vamp-fueled version of “Roxanne” that put plenty of distance between it and karaoke territory featured all three instrumentalists diving into their respective toolboxes. Yet for all the superior chemistry and musicianship at hand, the concert resonated on an altogether deeper level due to its opening and closing selections.

Whether they were intentionally sequenced or intended to subtly convey crucial themes at this particularly fraught moment in history remains only known to Sting. Yet via their mentions of shared loneliness (“Message in a Bottle”), politicians who resemble “game show hosts” (“If I Ever Lose My Faith in You”) and legal aliens (“Englishman in New York”), the first three songs came across as unmistakably relevant and timely.

As did the finale. Trading his electric bass for an acoustic guitar on “Fragile,” Sting stated he wanted to leave everyone with a contemplative piece. “Nothing comes from violence / And nothing ever could,” he sang, the statement ringing with fierce truth as election day draws nearer.

Fragile, indeed. A perilous condition that describes the state of our country, and the song’s premise functioning as wise advice to remember in the ensuing weeks.

(c) The Chicago Tribune by Bob Gendron