Sting came to Melbourne and had everyone dancing (politely) in the aisles...

It’s easy to be cynical about Sting.

As frontman of The Police, he was one of the coolest exports of the British New Wave. As a solo artist, he became a byword for a unique brand of cringe. His strident human-rights activism, startling turn as an actor (and even more alarming metallic codpiece in the original Dune), his enthusiasm for tantric sex – all while purveying his searchingly earnest soft-rock –made him an easy target for ridicule.

And yet, Sting slaps. This tour is named My Songs, and it showcases decades of songcraft. Some of those songs are among pop’s greatest. Some are not; but that’s hardly the point of the night.

The set opened with Message in a Bottle, then slipped into the radio staple Englishman in New York, before a delightful up-tempo slice of Every Little Thing She Does is Magic. A bravura opening – including a drum breakdown/call and response section during Englishman that felt only a little mega-churchy – had the audience dancing (politely) in the aisle. It was hard to spot someone in the crowd who did not know every lyric, a fact Sting acknowledged, thanking everyone for singing along nicely, before launching, somewhat apologetically, into new material.

No matter, the crowd dutifully took their seats for a few down-tempo selections from The Bridge (2021), then pogoed up again for a bracing version of So Lonely, which segued into a cover of No Woman No Cry.

For nearly two hours, Sting’s vocals never tired. The plaintive thirst of Fields of Gold, the rasp in Roxanne, the Arabic-language intro to Desert Rose originally sung by Cheb Mami – Sting nailed them all. Occasional vocal slips were smoothed by carefully supportive backing vocalists, who also provided virtuosic R&B and gospel vocal showcases.

It has to be noted that throughout the night Sting had the crowd, to paraphrase a lyric from the charming bric-a-brac of the setlist, wrapped around his finger. The years have been kind to Sting, but kinder to his music. His brand of mature vulnerability – that read as a sort of protean soft-boy cringe back in the jaded days of Fukuyama’s End of History – feels more welcome in today’s callous world, where authenticity and connection come at a premium.

This is a performer who kept ploughing ahead until the world was ready for him, a sort of pop-cultural tantric session. For a musician to reach this sort of a climax so late in a career, well, it’s a kind of magic.

(c) The Age by Liam Pieper

Sting: My Songs Tour – Rod Laver Arena, Melbourne, February 23rd 2023 – Live Review...

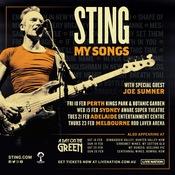

As a kid, I grew up listening to Queen, Bryan Adams, and The Police. Cut to the 26th of January 2008 and I was finally seeing The Police on their reunion tour at the MCG. Move forward to the 23rd of February 2023, and I would be seeing Sting for the first time in 15 years at the iconic Rod Laver Arena as part of his My Songs Tour.

Supported by his son Joe Sumner with musical talents that have rubbed off from his father in all the right ways (Sumner even doing a duet during his set with Something For Kate’s Paul Dempsey, and being stoked to be at Rod Laver Arena after watching Andy Murray play tennis there so many times), and accompanied by a 6-piece electric ensemble, British singer-songwriter and all-round music legend Sting kicked off his Melbourne leg of the tour with a Police classic, ‘Message In A Bottle’. Although I was excited to hear songs from The Police era, I was even more keen to hear Sting’s solo songs, most of which I’ve not heard live before.

‘Englishman In New York’ is just so groovy and catchy, it had fans singing along in an instant. There was just something so comforting about hearing everyone else in the venue also singing the lyrics, “Oh, I’m an alien, I’m a legal alien, I’m an Englishman in New York”. In that moment, I was so content, I was beaming, and this was only the second song of the night!

What I loved most about seeing Sting live was the fact that he had a microphone headset instead of the traditional handheld microphone and stand. This provided Sting freedom to roam the stage, and roam he did! It’s something so simple, but genius, and I don’t know why more artists don’t do it this way.

During the show, Sting’s interactions with the Melbourne audience felt, genuine, personal and intimate. He would mention life experiences that would expertly lead to the next song he was going to play. Sharing stories of love, friendship, and songwriting, Sting mentioned owning a ‘castle’ that’s just a stone throw away from Stonehenge, and that if anyone is ever in town they’d be welcome to come over for a cup of tea – but he’d be on tour.

But my favourite little tale of the night was Sting’s friendship with Melbourne’s own late-great Michael Gudinski and sharing that he was emotional when he saw Gudinski’s bronze statue outside the Rod Laver Arena venue. Sting had mentioned how the two had been friends since the 80s, but that’s not hard to imagine, considering what a titan Gudinski was for music in Australia.

Sting’s solo career is probably the most musically diverse I’ve seen of any artist, with elements of rock, jazz, new-age, classical, and reggae. But at Sting’s Melbourne show, no matter the song, every different tune and style suited his voice. His impressive vocals appeared to be executed with such ease. He also looked so happy to be performing in Melbourne, as much as the Melbourne crowd were happy to see his return.

Sting relished in sharing the spotlight with his band. A highlight would be Shane Sager stepping into Stevie Wonder’s shoes to artfully play the harmonica parts of ‘Brand New Day’. Sting also shared the stage with his son Joe Sumner to ‘King of Pain’.

However, my favourite songs performed of Sting’s solo work were ‘Fields of Gold’, ‘Fragile’, and ‘Desert Rose’. I remember ‘Desert Rose’ during its initial release receiving mixed reactions about its North African roots. But the song was ahead of its time and is, I dare say, a musical masterpiece.

As a fan of The Police, I was overjoyed to hear my favourite song ‘So Lonely’. Not only is it infectiously catchy, but the song was once my ringtone, so whenever people would ring, I would assume they’d be lonely (pun intended).

There are many artists that sound great on record, but Sting sounds even better live. There’s a sincerity to his performance that is just so endearing to witness. By the end of the night, after performing the one number that everyone was hungry for – ‘Roxanne’, the entire venue crowd was up on their feet and dancing. They also provided the humble singer a standing ovation when he bid farewell to the ever attentive and appreciative Melbourne audience.

As the night was ending, I couldn’t help but feel emotional about how lucky we all were to be in that venue to witness the talents of this fantastic human. I was also so grateful to be alive and old enough to see with my own eyes, hear with my own ears, and appreciate Sting. There are so many artists that have lived and have left us that I wasn’t old enough to see. So, as a big music fan, and as a writer, I am very thankful that the stars aligned.

(c) Lilithia.net by Stephanie Chin