Selected Miscellaneous Shows

Jul

13

1985

London, GB

Live Aid (Wembley Stadium)

Live Aid 1985: A Day of Magic...

"The sun was shining ... so were the people, and so were the bands," U2's Bono said after coming off stage, one of the undoubted major stars of "The Global Jukebox," Live Aid 1985.

"There was something totally unique and I am not sure I've ever felt it since," the man who kicked off Live Aid, Francis Rossi of Status Quo, told The Observer newspaper.

"They weren't just people paying to see a show. They were part of it. There was such a euphoric feeling in that arena."

With wife Lynne I was lucky enough to be part of the 72,000-strong audience at London's Wembley Stadium for what became one of Britain's most treasured days.

For once the reality trounced the build-up. It was much, much bigger than the publicity. Few music fans will forget what they were doing on July 13, 1985.

It didn't make poverty history in Ethiopia but, along with memories of U2, Queen, Madonna, The Who, Elton, George Michael, Bowie, Jagger and McCartney, everyone who watched will still shed a tear recalling that haunting Canadian video of starving, dying Ethiopian children played to "Drive" by Cars ("Who's going to take you home tonight?").

There had been other big rock and pop benefits, of course, like the Concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden in 1972.

But Bob Geldof's genius was to use the latest TV satellite technology to link up Wembley in north London, JFK Stadium in Philadelphia and a host of smaller venues in other countries to blitz the world's TV networks.

It was the first truly global concert, and people felt empowered and exhilarated. They felt they really could help change the world.

About 1.9 billion viewers in 150 countries - the biggest-ever TV audience - watched. Promoter Harvey Goldsmith believed it would raise $1 million. The real figure was $70 million, later to reach $140 million in total. Super-conjuror Geldof's plans may have been improbably mega-scale, but they worked.

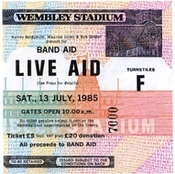

If it wasn't quite the hottest, it was the longest day I can remember - beginning with an 8 a.m. Saturday dash to Wembley to scramble into the stadium to try and claim a prime spot.

It ended with watching the finale in Philadelphia on TV at 4:05 a.m. Sunday, a full 20 hours later - a day played out in both Britain and the U.S. in glorious sunshine and in a mood of electric energy, hope and goodwill.

So what was different back in 1985?

Well, for a start then it was much easier to get tickets. Lynne got down to the Wembley box office when they went on sale and had to queue for a massive 15 minutes.

Probably the most important difference is then, there were no mobiles, no texts, no camera phones. We were locked inside Wembley incommunicado with the outside world, not knowing how massive was the event we had become part of.

David Hepworth, one of the BBC's anchors for the event, told CNN: "You just thought, I'm in here, it's hot, all these bands playing, it appears to be going rather well.

"It was only went you went home (and) my wife said, 'That was astonishing!'"

Prior to the 1985 event, not everyone had seen it as one of the biggest shows of all time. I told one of the chiefs at the paper where I worked that I was going to Live Aid, and would he like a piece for Monday's edition. No, he said, the Sunday papers would do it and no one would be much interested by Monday. But they are still writing about it 20 years later! (My former paper was advertising a Live 8 special section this week).

The slightly ramshackle organization in 1985 (would you believe they were only selling three items of memorabilia - the program, a poster and a T-shirt?) added to the buzz. Just how would it go?

In the stadium beneath two monster Live Aid graphics in the agonizing two-hour wait for the show to go on, no one had thought of warming up the crowd to keep folks in good humor. The mood was, well, tense. An American in front of me stood up and announced we were going to do "the wave." He was met by a stream of abuse telling him, with Geldof-type expletives, to sit down, followed by a hail of bottles. A direct hit on the head from an apple knocked him over and he gave up.

Then, if I recall correctly, someone had the bright idea of putting on a Beach Boys tape. The crowd sang, "the wave" got going, Prince Charles and Princess Diana were greeted with a fanfare of trumpets. By the time Status Quo got things moving just after midday with "Rocking All Over the World," the crowd was in a fine mood. It just grew and grew from there.

How Geldof persuaded so many super rock star egos to come off after just 17 minutes each I don't know.

The great man himself appeared for a few little chats, conducting himself with unexpected decorum (i.e., no swearing). To say this was not your average rock concert audience is an understatement. No indie, cutting edge or boy bands, so the audience was rather 25-35, white and middle class. Some people had arrived with hampers and spread out blankets in front of the stage, summer opera concert style, thinking they could claim that as their space! (They were soon disabused).

After Geldof's set, the crowd sang to him... the well-known heavy metal anthem, "For he's a jolly good fellow." "For he's a jolly good fellow." Honest.

The Boomtown Rats singer made his own point about the dying in Ethiopia when he got to a line in "I don't like Mondays" which goes, "And the lesson today is how to die" and stopped abruptly, raising his fist in the air.

But it was still touch and go. Many of the opening acts were people who had agreed to sing on Geldof and Midge Ure's record "Do they know it's Christmas?" and that early part of the Wembley action had a bit of a second-on-the-bill feel to it.

U2 changed all that.

This was the moment which assured the band its place in history. In what seemed an endless 12-minute rendition of "Bad" (with bits of the Rolling Stones and Lou Reed thrown in) Bono - somewhat uncomfortably dressed for a hot day in black coat, black leather trousers and knee length black boots - vaulted down into the photographer's pit to dance with a young girl fan.

He knew how to connect with the audience. The crowd went wild.

The show-stopping performance of the day, as everyone knows by now, was Freddie Mercury of Queen. The group had rehearsed their set for a week, and it showed.

They began with "Bohemian Rhapsody" and "Radio Ga Ga" and ended with "We Will Rock You" and "We Are The Champions" - with the whole crowd singing along. It was a triumph for Freddie, one which he repeated by filling Wembley 364 days later for a Queen concert. I was there too, and he was superb. Sadly 1986 was his last big performance.

There were some rather crazy live video links to unheard-of bands in distant places like Warum at "Austria for Afrika" in Vienna, plus videos from Yugoslavia and Norway. But things had started to really rock when, at 5 p.m. London time, 1200 ET, the link went to Jack Nicholson in Philadelphia and he introduced Bryan Adams (would you believe Ozzy Ozbourne had gone on at JFK at the non-very heavy metal time of 9:52 a.m.?).

U2, Dire Straits and Queen followed in quick succession at Wembley followed by showing of the the Bowie-Jagger video "Dancing in the Street." Rumor had it they wanted to do a duet, Bowie in Wembley and the ex-Stone in JFK ... then someone remembered the little matter of the several-second satellite sound transmission gap.

Soon after that, Bowie changed the mood. He had given up the last song in his allotted 20 minutes to make way for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's video on the Ethiopia famine, song by Cars. Many people wept.

Then The Who (reunited somewhat kicking and screaming for the event) came on. I recall they were very tense, glowering at each other, but blasted out "My Generation" and "Pinball Wizard" like there was no tomorrow. (I read subsequently the BBC blew a fuse in its U.S. transmission appropriately when Daltry got to: "Why don't you all f-f-fade away.")

Elton John was next - wearing a silly hat, I remember, but pleasing the crowd rattling through old favorites like "Bennie and the Jets" and "Rocket Man."

As an unbelievable A-list of rock icons was rolled out, it is well to remember who didn't turn up in either the UK or the U.S. to give their services for free. Three big stars of the time weren't there - Michael Jackson, Bruce Springsteen and Prince, though Prince sent a video.

Two of the three surviving Beatles, George Harrison and Ringo Starr, didn't show, according to the unofficial Live Aid Web site, apparently fearful of being forced into a Beatles "reunion" with Julian Lennon taking the fourth spot.

But that didn't stop The Who reuniting ("An offer we couldn't refuse," Roger Daltrey said) or the Stones turning up in Philadelphia and performing separately. Holly Johnson of Frankie Goes to Hollywood said later it was a disastrous decision by his band not to take part, and Stevie Wonder has made sure he is there in Philadelphia this time.

Much was made in '85, particularly in the TV coverage, of Phil Collins' dash from Wembley to JFK on Concorde. (Quote of the day: "I was in England this afternoon. Funny old world, innit.")

The plane flew over Wembley and dipped its wings in salute. Collins gave faultless performances at both venues, at JFK appearing with Eric Clapton and then Robert Plant and Jimmy Page, as well as on his own. You had to admire his guts.

The last of the three most memorable Wembley performances of the day was by George Michael, then part of the duo Wham! He sang his part of "Don't Let The Sun Go Down On Me" with Elton and Andrew Ridgeley majestically. He could do well as a solo artist, I remember thinking.

It was now rather dark and a man appeared at a grand piano and began playing but his microphone wouldn't work. Who was this? Ah yes, it was Paul McCartney trying to do "Let it Be." To think of, it with those tight turnarounds and lack of sound checks, it was a wonder there weren't many more technical foul-ups like this. The crowd sportingly sung the song for him until the mike was finally activated after two minutes.

The Wembley finale then followed with the most glittering array of famous names since they made the cover for "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Heart's Club Band" - and this time they were real people. They sung "Don't They Know It's Christmas" before McCartney and Pete Townsend hauled Geldof onto their shoulders. A fitting climax.

That was not the case in Philadelphia where, in front of a larger crowd of 90,000, Lionel Ritchie led singing of "We Are The World," and Harry Belafonte - rather than the Jaggers and Dylans of this world - was somehow focus for the camera.

We had dashed home from Wembley to see the Philadelphia concert on TV, not doing too badly in terms of acts missed and arriving in the middle of The Cars singing "Heartbreak City." I bought the LP. Then a young Madonna prancing around the stage with The Thomson Twins singing "Revolution." How young she looks now when you watch the recording - and how brunette.

This was the best part of the U.S. program. Eric Clapton rendered a powerful "She's Waiting" and "Layla."

Robert Plant and Jimmy Page were playing together for the first time since the death of drummer John Bonham five years earlier, but they weren't billed as Led Zeppelin. They didn't allow their set to go out on the recent CD because they didn't think it was up to scratch. Sorry, but I thought they were great.

"Any requests?" asked Plant, knowing full well the answer. "Whole Lotta Love" and "Stairway to Heaven" - said to be the most requested record of all time - would do just fine by us.

Then to Mick Jagger and Tina Turner writhing to "It's Only Rock and Roll." What can I say? Two cats on hot bricks, and one of the enduring Live Aid images. She said afterwards she had stamped her high heel on his foot. Something clearly got him going, though he seemed to have visited a rather eccentric tailor to buy his outfit.

Nearly the end in Philadelphia. Enter Bob Dylan, who sparked a row by suddenly suggesting that some of the money raised should go to American farmers. On this day of rocking internationalism his bit of U.S. nationalism was considered by Geldof "crass." They held a separate Farm Aid concert later that year, which was a much better thought.

Dylan was said to have bumped Peter, Paul and Mary to be backed for "Blowing in the Wind" on acoustic guitar by Rolling Stones Ronnie Wood and Keith Richards. To say they looked tired would be an understatement. Richard banged the microphone with his guitar. Wood seemed to take a dislike to his instrument and kept trying to hand it to someone backstage.

Never mind, the good news from the BBC was that $3 million had been raised already to try to help victims of the Ethiopia famine - a figure which was to rise to $140 million by the time the charity was dissolved in 1992.

Jools Holland said during one of the TV links that he had been driving through London and, on this hot summer night, the sounds of Live Aid were blasting out from every bar in the city. Midge Ure later reported a street party atmosphere with people inviting neighbors and even complete strangers into their homes.

We finally got to bed at 4 a.m. - pure magic. A day never to forget.

"It was one of those events. ...People wanted to feel something - and all feel it together."

Gary Kemp of Spandau Ballet told The Observer: "There was this sense of a grand event going on that could equal England winning the World Cup in 1966 or the Coronation of 1953.

"This is something that would be stamped on everybody. It is a day when, no matter how young you were, you remembered where you were."

(c) CNN.com by Graham Jones

"The sun was shining ... so were the people, and so were the bands," U2's Bono said after coming off stage, one of the undoubted major stars of "The Global Jukebox," Live Aid 1985.

"There was something totally unique and I am not sure I've ever felt it since," the man who kicked off Live Aid, Francis Rossi of Status Quo, told The Observer newspaper.

"They weren't just people paying to see a show. They were part of it. There was such a euphoric feeling in that arena."

With wife Lynne I was lucky enough to be part of the 72,000-strong audience at London's Wembley Stadium for what became one of Britain's most treasured days.

For once the reality trounced the build-up. It was much, much bigger than the publicity. Few music fans will forget what they were doing on July 13, 1985.

It didn't make poverty history in Ethiopia but, along with memories of U2, Queen, Madonna, The Who, Elton, George Michael, Bowie, Jagger and McCartney, everyone who watched will still shed a tear recalling that haunting Canadian video of starving, dying Ethiopian children played to "Drive" by Cars ("Who's going to take you home tonight?").

There had been other big rock and pop benefits, of course, like the Concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden in 1972.

But Bob Geldof's genius was to use the latest TV satellite technology to link up Wembley in north London, JFK Stadium in Philadelphia and a host of smaller venues in other countries to blitz the world's TV networks.

It was the first truly global concert, and people felt empowered and exhilarated. They felt they really could help change the world.

About 1.9 billion viewers in 150 countries - the biggest-ever TV audience - watched. Promoter Harvey Goldsmith believed it would raise $1 million. The real figure was $70 million, later to reach $140 million in total. Super-conjuror Geldof's plans may have been improbably mega-scale, but they worked.

If it wasn't quite the hottest, it was the longest day I can remember - beginning with an 8 a.m. Saturday dash to Wembley to scramble into the stadium to try and claim a prime spot.

It ended with watching the finale in Philadelphia on TV at 4:05 a.m. Sunday, a full 20 hours later - a day played out in both Britain and the U.S. in glorious sunshine and in a mood of electric energy, hope and goodwill.

So what was different back in 1985?

Well, for a start then it was much easier to get tickets. Lynne got down to the Wembley box office when they went on sale and had to queue for a massive 15 minutes.

Probably the most important difference is then, there were no mobiles, no texts, no camera phones. We were locked inside Wembley incommunicado with the outside world, not knowing how massive was the event we had become part of.

David Hepworth, one of the BBC's anchors for the event, told CNN: "You just thought, I'm in here, it's hot, all these bands playing, it appears to be going rather well.

"It was only went you went home (and) my wife said, 'That was astonishing!'"

Prior to the 1985 event, not everyone had seen it as one of the biggest shows of all time. I told one of the chiefs at the paper where I worked that I was going to Live Aid, and would he like a piece for Monday's edition. No, he said, the Sunday papers would do it and no one would be much interested by Monday. But they are still writing about it 20 years later! (My former paper was advertising a Live 8 special section this week).

The slightly ramshackle organization in 1985 (would you believe they were only selling three items of memorabilia - the program, a poster and a T-shirt?) added to the buzz. Just how would it go?

In the stadium beneath two monster Live Aid graphics in the agonizing two-hour wait for the show to go on, no one had thought of warming up the crowd to keep folks in good humor. The mood was, well, tense. An American in front of me stood up and announced we were going to do "the wave." He was met by a stream of abuse telling him, with Geldof-type expletives, to sit down, followed by a hail of bottles. A direct hit on the head from an apple knocked him over and he gave up.

Then, if I recall correctly, someone had the bright idea of putting on a Beach Boys tape. The crowd sang, "the wave" got going, Prince Charles and Princess Diana were greeted with a fanfare of trumpets. By the time Status Quo got things moving just after midday with "Rocking All Over the World," the crowd was in a fine mood. It just grew and grew from there.

How Geldof persuaded so many super rock star egos to come off after just 17 minutes each I don't know.

The great man himself appeared for a few little chats, conducting himself with unexpected decorum (i.e., no swearing). To say this was not your average rock concert audience is an understatement. No indie, cutting edge or boy bands, so the audience was rather 25-35, white and middle class. Some people had arrived with hampers and spread out blankets in front of the stage, summer opera concert style, thinking they could claim that as their space! (They were soon disabused).

After Geldof's set, the crowd sang to him... the well-known heavy metal anthem, "For he's a jolly good fellow." "For he's a jolly good fellow." Honest.

The Boomtown Rats singer made his own point about the dying in Ethiopia when he got to a line in "I don't like Mondays" which goes, "And the lesson today is how to die" and stopped abruptly, raising his fist in the air.

But it was still touch and go. Many of the opening acts were people who had agreed to sing on Geldof and Midge Ure's record "Do they know it's Christmas?" and that early part of the Wembley action had a bit of a second-on-the-bill feel to it.

U2 changed all that.

This was the moment which assured the band its place in history. In what seemed an endless 12-minute rendition of "Bad" (with bits of the Rolling Stones and Lou Reed thrown in) Bono - somewhat uncomfortably dressed for a hot day in black coat, black leather trousers and knee length black boots - vaulted down into the photographer's pit to dance with a young girl fan.

He knew how to connect with the audience. The crowd went wild.

The show-stopping performance of the day, as everyone knows by now, was Freddie Mercury of Queen. The group had rehearsed their set for a week, and it showed.

They began with "Bohemian Rhapsody" and "Radio Ga Ga" and ended with "We Will Rock You" and "We Are The Champions" - with the whole crowd singing along. It was a triumph for Freddie, one which he repeated by filling Wembley 364 days later for a Queen concert. I was there too, and he was superb. Sadly 1986 was his last big performance.

There were some rather crazy live video links to unheard-of bands in distant places like Warum at "Austria for Afrika" in Vienna, plus videos from Yugoslavia and Norway. But things had started to really rock when, at 5 p.m. London time, 1200 ET, the link went to Jack Nicholson in Philadelphia and he introduced Bryan Adams (would you believe Ozzy Ozbourne had gone on at JFK at the non-very heavy metal time of 9:52 a.m.?).

U2, Dire Straits and Queen followed in quick succession at Wembley followed by showing of the the Bowie-Jagger video "Dancing in the Street." Rumor had it they wanted to do a duet, Bowie in Wembley and the ex-Stone in JFK ... then someone remembered the little matter of the several-second satellite sound transmission gap.

Soon after that, Bowie changed the mood. He had given up the last song in his allotted 20 minutes to make way for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's video on the Ethiopia famine, song by Cars. Many people wept.

Then The Who (reunited somewhat kicking and screaming for the event) came on. I recall they were very tense, glowering at each other, but blasted out "My Generation" and "Pinball Wizard" like there was no tomorrow. (I read subsequently the BBC blew a fuse in its U.S. transmission appropriately when Daltry got to: "Why don't you all f-f-fade away.")

Elton John was next - wearing a silly hat, I remember, but pleasing the crowd rattling through old favorites like "Bennie and the Jets" and "Rocket Man."

As an unbelievable A-list of rock icons was rolled out, it is well to remember who didn't turn up in either the UK or the U.S. to give their services for free. Three big stars of the time weren't there - Michael Jackson, Bruce Springsteen and Prince, though Prince sent a video.

Two of the three surviving Beatles, George Harrison and Ringo Starr, didn't show, according to the unofficial Live Aid Web site, apparently fearful of being forced into a Beatles "reunion" with Julian Lennon taking the fourth spot.

But that didn't stop The Who reuniting ("An offer we couldn't refuse," Roger Daltrey said) or the Stones turning up in Philadelphia and performing separately. Holly Johnson of Frankie Goes to Hollywood said later it was a disastrous decision by his band not to take part, and Stevie Wonder has made sure he is there in Philadelphia this time.

Much was made in '85, particularly in the TV coverage, of Phil Collins' dash from Wembley to JFK on Concorde. (Quote of the day: "I was in England this afternoon. Funny old world, innit.")

The plane flew over Wembley and dipped its wings in salute. Collins gave faultless performances at both venues, at JFK appearing with Eric Clapton and then Robert Plant and Jimmy Page, as well as on his own. You had to admire his guts.

The last of the three most memorable Wembley performances of the day was by George Michael, then part of the duo Wham! He sang his part of "Don't Let The Sun Go Down On Me" with Elton and Andrew Ridgeley majestically. He could do well as a solo artist, I remember thinking.

It was now rather dark and a man appeared at a grand piano and began playing but his microphone wouldn't work. Who was this? Ah yes, it was Paul McCartney trying to do "Let it Be." To think of, it with those tight turnarounds and lack of sound checks, it was a wonder there weren't many more technical foul-ups like this. The crowd sportingly sung the song for him until the mike was finally activated after two minutes.

The Wembley finale then followed with the most glittering array of famous names since they made the cover for "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Heart's Club Band" - and this time they were real people. They sung "Don't They Know It's Christmas" before McCartney and Pete Townsend hauled Geldof onto their shoulders. A fitting climax.

That was not the case in Philadelphia where, in front of a larger crowd of 90,000, Lionel Ritchie led singing of "We Are The World," and Harry Belafonte - rather than the Jaggers and Dylans of this world - was somehow focus for the camera.

We had dashed home from Wembley to see the Philadelphia concert on TV, not doing too badly in terms of acts missed and arriving in the middle of The Cars singing "Heartbreak City." I bought the LP. Then a young Madonna prancing around the stage with The Thomson Twins singing "Revolution." How young she looks now when you watch the recording - and how brunette.

This was the best part of the U.S. program. Eric Clapton rendered a powerful "She's Waiting" and "Layla."

Robert Plant and Jimmy Page were playing together for the first time since the death of drummer John Bonham five years earlier, but they weren't billed as Led Zeppelin. They didn't allow their set to go out on the recent CD because they didn't think it was up to scratch. Sorry, but I thought they were great.

"Any requests?" asked Plant, knowing full well the answer. "Whole Lotta Love" and "Stairway to Heaven" - said to be the most requested record of all time - would do just fine by us.

Then to Mick Jagger and Tina Turner writhing to "It's Only Rock and Roll." What can I say? Two cats on hot bricks, and one of the enduring Live Aid images. She said afterwards she had stamped her high heel on his foot. Something clearly got him going, though he seemed to have visited a rather eccentric tailor to buy his outfit.

Nearly the end in Philadelphia. Enter Bob Dylan, who sparked a row by suddenly suggesting that some of the money raised should go to American farmers. On this day of rocking internationalism his bit of U.S. nationalism was considered by Geldof "crass." They held a separate Farm Aid concert later that year, which was a much better thought.

Dylan was said to have bumped Peter, Paul and Mary to be backed for "Blowing in the Wind" on acoustic guitar by Rolling Stones Ronnie Wood and Keith Richards. To say they looked tired would be an understatement. Richard banged the microphone with his guitar. Wood seemed to take a dislike to his instrument and kept trying to hand it to someone backstage.

Never mind, the good news from the BBC was that $3 million had been raised already to try to help victims of the Ethiopia famine - a figure which was to rise to $140 million by the time the charity was dissolved in 1992.

Jools Holland said during one of the TV links that he had been driving through London and, on this hot summer night, the sounds of Live Aid were blasting out from every bar in the city. Midge Ure later reported a street party atmosphere with people inviting neighbors and even complete strangers into their homes.

We finally got to bed at 4 a.m. - pure magic. A day never to forget.

"It was one of those events. ...People wanted to feel something - and all feel it together."

Gary Kemp of Spandau Ballet told The Observer: "There was this sense of a grand event going on that could equal England winning the World Cup in 1966 or the Coronation of 1953.

"This is something that would be stamped on everybody. It is a day when, no matter how young you were, you remembered where you were."

(c) CNN.com by Graham Jones